Clearly, I am an advocate for bus mechanics. It has a tremendous amount of advantages, significantly so when the items on the bus have an infinite shelf life. It saves you from spaghetti factories, allows for improved logistics, and overall more efficient use of material. With that, there are some interesting downsides that really only start to show in specific cases.

Available Space

Bus architecture is on the whole smaller than dedicated lanes, but it also comes with larger space requirements. 15 small paths take up more overall space than 1 large one, but that large path cannot be deviated. If you have mines, water, or obstacles in the way, you may not be able to build the bus. Satisfactory solves this with vertical factories. DSP can pave over planets. Factorio has this issue when you leave the main planet, which can certainly be mitigated through cliff explosives, landfill and ice.

Item Queues

A bus generally operates on a saturation model, where all parts are full. Any item on the bus is one that is not being actively used, and therefore you have a major buffer of items. This is good to manage burst demands, but can be bad when you have very expensive items sitting idle on the bus. This is a major issue if the items on the bus can expire, as the time to travel / wait, can cause it to spoil. Satisfactory will have a massive bus and a giant ‘waste’ of materials (which are infinite, so you’re wasting time). DSP doesn’t really have too much of a problem here as the ratios generally are in your favor. Factorio only has issues here with items that expire, mainly Gleba items.

Accuracy

The greatest benefit of a bus is the flexibility and simplicity of use. You can clearly see with your eyes if it’s working as an empty bus = not going well. The solution to an empty bus is relatively simple, add a bunch of items to it at the start until it backs up. No math, nothing fancy, just jam it full of stuff.

The flipside to this is that it becomes increasingly expensive to scale the end result items as each individual item on the bus may cause bottlenecks. Or, you may simply run out of space and need large scale transport logistics. In these cases, it’s often better to build mini-factories that are offshoots of the bus, especially in late game aspects. The net benefit of this model is that the input and outputs are controlled, and easily replicated with blueprints.

- Satisfactory is very binary here, as you either make mini factories from the start or you make a bus all the way through, simply because there are too many items. You may end up using this model for a Nuclear factory though, even though it will take about 20 or so different ingredients to work. The lack of large scale blueprints absolutely prevents effective use of factories. You can make them for sure, but it’s going to be hours of effort. If the production chains weren’t so complex…a Ficsite Bar for a power plant has about 30 different production steps.

- DSP’s bus is very different as there are 2 buses. One for buildings, of which you won’t ever build factories for. Another for everything else with Logistic Stations – which is like watching mosquitos fly around, moving items between towers feeding dozens of mini-factories. For late game, when focusing on SPM, there is some value in building factories dedicated for this as you can ‘easily’ increase your SPM by putting down a new blueprint. The game is extremely modular and flexible in this regard, with the absolute best production dashboard information around. An analyst’s dream.

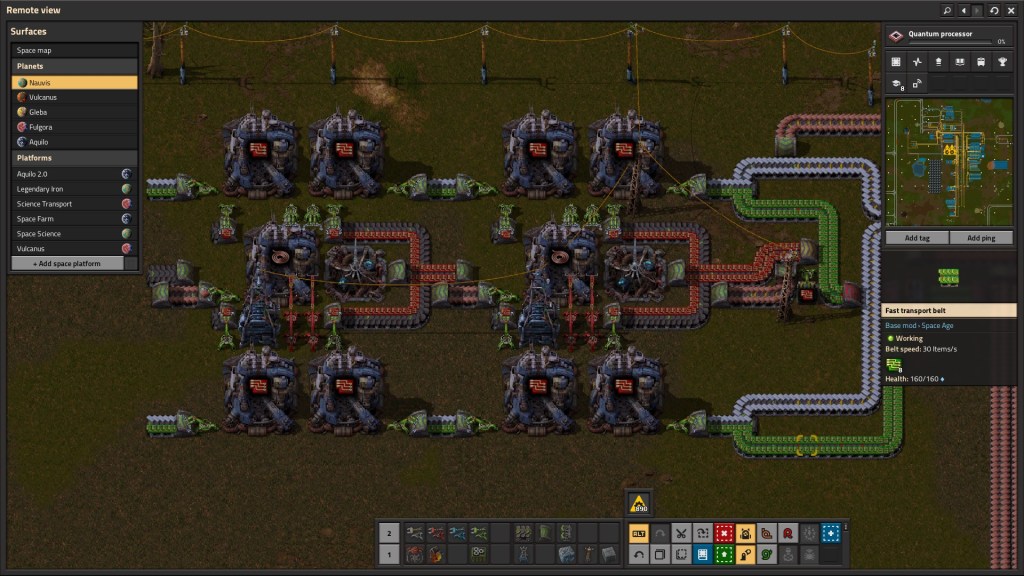

- Factorio’s bus is such that you will only ever have mini-factories. The bus itself is only ever relevant for items that are created in very high volumes. Where the starter planet may have a bus that feeds construction of buildings, this is absolutely not the case on the next planet as robots & requestors can address this for you. This is a net effect of simplified production chains, as compared to others. The casino portion of acquiring legendary material is a completely different topic highlighting the pitfalls of a bus, and while ‘fun’ to puzzle out an optimized method, absolutely sucks.

More Positives than Negatives

While there are niche cases where a bus is not particularly useful as the volume of items created are highly specialized (e.g. Nuclear Plants in Factorio), the wide majority benefit from a main bus for common refined raw material (e.g. the step just after raw material such as iron plates). Normally this main bus has 6-8 item types, generally in the space of iron, copper, coal, oil, then 2 more liquids and solids.

Full buses are different, where all items that have more than 2 uses are put on the belt. For some games, this means that the bus has 20 items. For others, 40+.

As a general rule, anytime I play a game with production elements, I opt to build some sort of bus in order to math out the long term requirements. They are relatively easy to build, provide a lot of flexibility, aesthetically please my eyes, and allow me to quickly diagnose production issues. Optimizing that bus would mean making it as small as possible, which really only comes from experimentation, knowing which items only have a short-term need. And with most of the games in this genre being in Early Access… well a patch can change a lot.

Plus, it’s fun to say bus.